Impact of Trump-Era Tariffs on U.S. Prices: Macroeconomic Trends and Industry Breakdown

Overview: Tariffs and Economy-Wide Price Pressures

The Trump administration’s new tariffs (2018–2019) introduced a significant cost shock to the U.S. economy, broadly raising prices, disrupting supply chains, and creating ripple effects across industries.[1 2] These tariffs – covering imported goods across all industries – effectively act as tax increases for U.S. firms and consumers. Studies of past tariffs confirm that new tariffs increase costs for U.S. businesses and consumers, contributing to higher inflation and dampening economic output.[1] In fact, the 2018–19 tariff rounds constituted one of the largest tax increases in decades, with the added duties raising about $142 billion (an average burden of over $1,000 per U.S. household).[1]

Crucially, evidence shows this cost largely impacted domestic companies and consumers: foreign exporters generally did not reduce prices to offset the tariffs, meaning U.S. importers and consumers paid with increased prices to cover the full import tax.[3] Domestic suppliers also responded by raising their own prices in tandem with the tariffed imports (taking advantage of reduced foreign competition).[3]

The result was broad-based upward pressure on prices – a direct driver of inflation in targeted goods – even as overall U.S. inflation remained moderate in that period. S&P Global economists estimated that the cumulative tariffs would induce a one-time 0.5–0.7% rise in consumer prices (CPI) if fully implemented.[4] In summary, tariff-related cost increases rippled through the economy, creating inflation, and much sharper price spikes in certain industries.

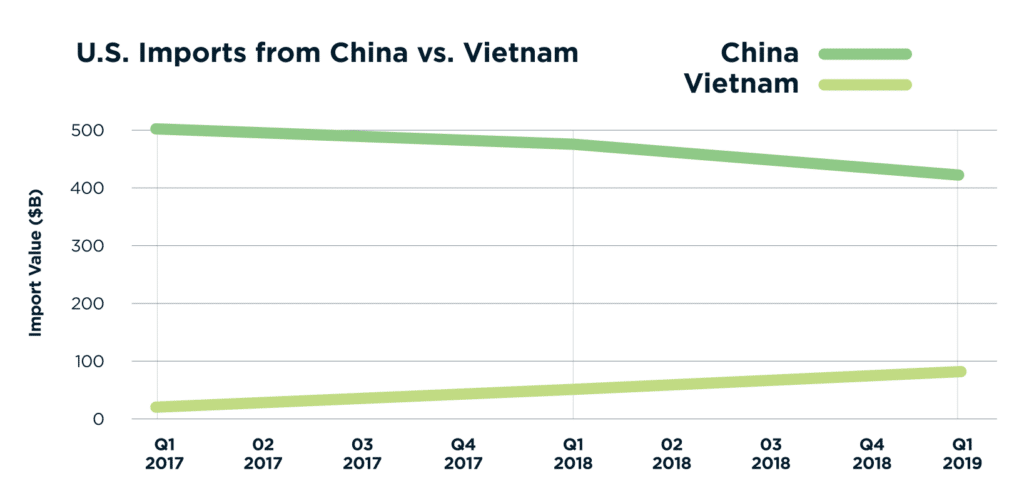

Beyond inflation, the tariffs triggered major supply chain adjustments. Import-dependent companies scrambled to mitigate the impact by shifting sourcing and production. By 2019, U.S. imports from China had dropped, replaced by imports from other countries or by domestic output. For example, analysts noted roughly $31 billion of U.S. import value shifted from China to other low-cost countries in 2019, with nearly half of that volume absorbed by Vietnam.[5] Many firms sought alternate suppliers in countries not subject to tariffs (e.g. moving manufacturing from China to Southeast Asia or Mexico).[2] Others accelerated efforts to source inputs domestically or build local inventory buffers to ride out price volatility. These shifts were costly and complex, often causing short-term disruptions. Tariff uncertainty led some businesses to front-load imports before tariffs hit, followed by supply gluts or gaps once duties went into effect. In summary, the trade war spurred a reorganization of supply chains, adding logistical inefficiencies and raising input costs during the transition.[2]

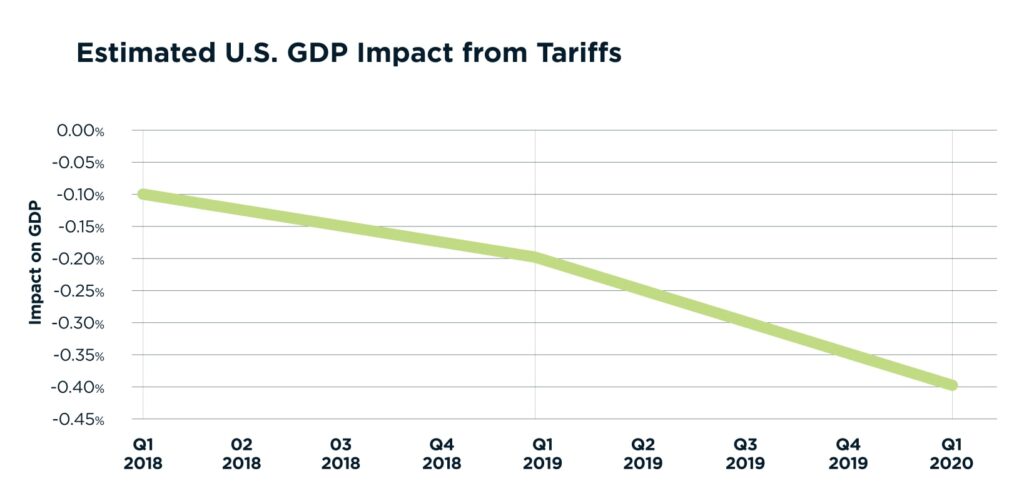

The broader economic ripple effects were significant. Higher import costs eroded U.S. firms’ profit margins or forced them to raise selling prices, potentially reducing demand. Retaliatory tariffs from trade partners (like China’s duties on U.S. exports such as agriculture) further distorted markets and hurt U.S. producers.[2] While protected industries (e.g. U.S. steel makers) saw temporary gains, downstream sectors lost competitiveness as their input costs climbed.[2] The net effect was a drag on growth – one analysis estimates the trade war tariffs (still largely in place) will reduce U.S. long-run GDP by about 0.2% and cost over 140,000 jobs.[1] In the context of pricing, these macro pressures translated into varying impacts across industries.

Below, we break down how product and service prices were affected in each major sector of interest, focusing on direct cost passthrough, changes in consumer pricing behavior, supply chain strategies, domestic vs. offshore sourcing shifts, and price elasticity considerations for each. The analysis emphasizes data-driven insights on how tariff-induced cost changes filtered into final prices.

Technology: Software, IT Hardware, and Electronics

Impact on costs

The tech sector felt a diverse impact. Pure software and digital services companies were largely insulated from direct tariffs, since their products (software, cloud services, digital media) aren’t physical goods crossing borders.[2] These firms did not face import taxes on their core outputs, so their pricing structures didn’t change due to tariffs.

However, segments of the tech industry that deal in hardware were exposed. Tariffs on Chinese electronics and components affected semiconductor producers, hardware manufacturers, and device assemblers. Key inputs like chips, circuit boards, displays, and telecom equipment faced duties (often 10–25%). This raised the production cost for finished tech products – from servers and networking gear to consumer devices like smartphones and gaming consoles. For instance, a 10% tariff on imported semiconductors or motherboards directly increased costs for U.S. PC and server manufacturers, potentially leading to higher prices for enterprise IT equipment.

Tech companies reliant on China for assembly (e.g. many smartphones and laptops) suddenly saw their U.S.-bound units taxed – a cost that amounted to billions across the sector. Some high-profile examples: Apple’s Apple Watch and AirPods were initially subject to tariffs, and while the iPhone was mostly spared in early rounds, it was threatened by later rounds (prompting lobbying for exclusions). Indirectly, even software-centric firms encounter higher prices for hardware they purchase (data center equipment, office computers, etc.), nudging up operating costs. Overall, while the digital side of tech was spared direct tariff costs, the hardware side experienced notable input cost inflation.

Price and market responses

In the short run, many tech companies tried to absorb tariff costs or find workarounds rather than immediately raise consumer prices, given how price-sensitive and globally competitive electronics markets are. For example, some consumer electronics brands accepted lower margins or made minor product modifications to mitigate the tariff hit (such as shipping products unassembled or via alternative ports). However, as tariffs persisted, price increases became unavoidable in some cases. Certain laptop and smartphone models saw price upticks or fewer promotional discounts than usual, effectively passing costs to consumers in a subdued way. Niche electronics (like high-end PC components) with less competition experienced more direct price hikes. Enterprise technology providers (selling to businesses/governments) often included tariff surcharges or adjusted contract pricing to reflect higher hardware costs. Importantly, the tech sector’s fast innovation cycle meant new product launches could factor in tariffs to pricing from the start, making the increase less apparent on legacy products.

Consumer behavior in tech tends to be somewhat inelastic for must-have devices (people still bought new phones, albeit perhaps with delays), but highly elastic for discretionary gadgets (some consumers held off on upgrades or switched to cheaper models when prices rose). One notable consumer behavior shift was a greater willingness to consider non-Chinese brands or devices produced outside China. For instance, if an iconic brand’s device became pricier due to tariffs, a consumer might opt for a competitor not hit by the same duties. Still, brand loyalty in tech is strong, so many paid the higher prices. Overall, tech product pricing did feel upward pressure, but the impact was moderated by strategic company responses and the partial rollback of certain tariffs under the 2020 Phase One trade deal (which reduced some duties from 15% to 7.5% on select consumer tech items).

Supply chain resilience and shifts

The global nature of the technology industry enabled relatively flexible adaptation to trade barriers. Major tech firms re-routed supply chains: for example, some electronics manufacturing for U.S. markets moved from China to Taiwan, Vietnam, or India to escape tariffs.[2] Companies like Google and Microsoft, which sell hardware (e.g. smart speakers, tablets), reportedly shifted more production to places like Taiwan and Southeast Asia.[2] Apple famously explored moving a portion of iPhone assembly to India and Mac production to the U.S. (or other countries) to reduce dependence on China.

These moves, however, take time and significant coordination with suppliers. In the interim, many tech firms relied on tariff exemptions – petitioning the U.S. government for product-specific exclusions (and indeed, quite a few tech components were temporarily exempted from tariffs to avoid disrupting consumer markets). Where exemptions weren’t granted, companies increased prices to compensate or bundled services to add value without directly hiking sticker prices.

Another strategy was inventory management: tech firms built up inventory of components before tariffs hit, then slowly drew it down, delaying the impact on production costs. Over the longer term, the trade war reinforced a trend of tech supply chain diversification: China’s dominance in electronics manufacturing began to erode slightly as alternatives gained share (e.g. Vietnam’s electronics exports to the U.S. surged, as noted, capturing a large chunk of shifted production).[5]

In terms of domestic vs. international sourcing, the highly specialized nature of tech manufacturing meant that much production stayed international but was redistributed among countries. Only a limited amount of assembly returned to the U.S., largely for bulky items (like some server assembly or high-end semiconductor packaging) due to tariff avoidance. Supply chain disruptions in tech were less about complete stoppages and more about cost and location – the flow of gadgets continued, but from new places and often at higher cost.

Sector price elasticity and outlook

The tech sector’s pricing dynamics under tariffs highlight differing elasticities. Software and cloud services (sold by subscription or license) didn’t see tariff-driven price hikes; any price changes there were driven by market factors unrelated to import costs. Consumer electronics have a medium elasticity – consumers are sensitive to price but also view many devices as essential. This meant companies had some leeway to charge more, but only up to a point. If a popular $1000 smartphone faced a 10% tariff ($100 cost increase), the maker might split the difference – raising the price maybe by $50 and absorbing $50 – to avoid a full demand shock. Enterprise hardware and telecom equipment often have inelastic demand in the near term (a telecom company must buy routers regardless of a tariff), allowing those costs to pass through via higher contract prices or service fees, eventually trickling down to business service prices.

A key point is that many tech firms could leverage innovation and product differentiation to justify prices that include tariff costs – e.g. releasing a new model with better features at a slightly higher price that covers the tariff on the old model’s components. Going forward, the tech industry’s adaptive supply chain and the partial easing of tariffs on consumer tech mean that the worst inflationary impacts were somewhat capped. However, during the peak of the trade war, data showed U.S. import prices for affected electronics rose significantly, and U.S. businesses bore those costs.[3] The legacy of this period is a more resilient but possibly more costly tech supply chain, with companies now factoring in geopolitical risk (and potential tariffs) into sourcing – which could keep a bit of extra price “insurance” buffer built into tech product costs.

Manufacturing & Industrial Goods

Direct cost impacts

Manufacturing was among the hardest-hit sectors, as it relies heavily on imported inputs (metals, components) that became more expensive. Tariffs on steel and aluminum (25% and 10% respectively) instantly raised raw material costs for U.S. factories in industries like automotive, machinery, aerospace, and construction. Domestic steel producers benefited from protection but hiked prices substantially – U.S.-made steel prices became up to 41% more expensive in the wake of the tariffs.[6] This imposed higher costs on a broad range of downstream manufacturers. For example, building a typical car requires about half a ton of steel; a 25% steel tariff was estimated to add over $1,000 in cost per vehicle in raw materials alone.[7]

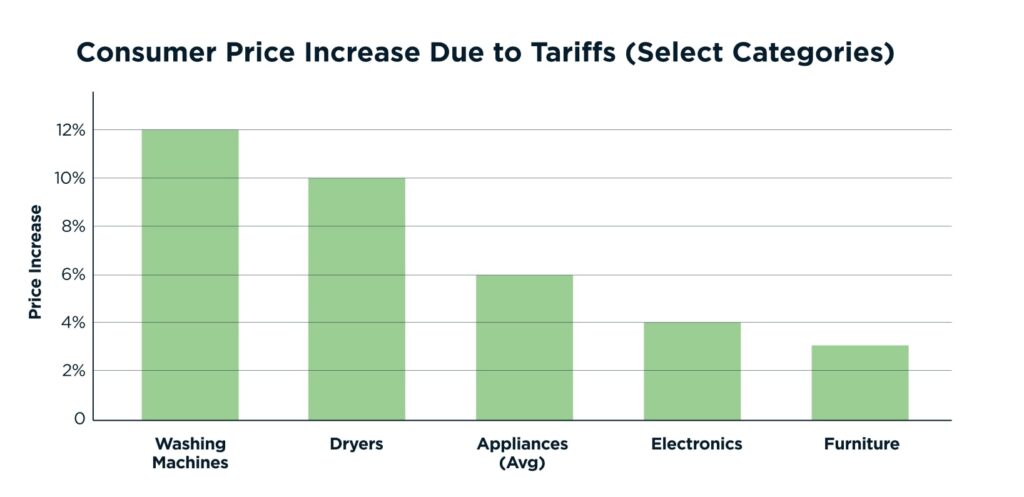

Automakers, appliance makers, and heavy equipment firms all faced similar input cost surges. In one well-documented case, tariffs of 20–50% on imported washing machines drove up U.S. appliance prices dramatically – washing machines saw a 12% price jump, and even dryers (not tariffed but often purchased together) rose in price by roughly 9% as manufacturers leveraged the reduced competition.[8] This study found over 100% of the tariff cost was passed through to consumers – and then some – as domestic producers also raised their prices.[8]

Such examples underscore the direct inflationary impact on manufactured goods: companies largely passed tariffs downstream. The U.S. International Trade Commission reported that in 2018, prices for steel and aluminum in the U.S. rose around 2% on average after the initial tariffs (with certain product categories far higher) while import volumes fell by about a quarter.[7] In practice, many manufacturers had no choice but to accept higher input costs, especially for specialized materials (e.g. high-grade steel, specific electronic parts) with few immediate substitutes.

Pricing strategy and consumer behavior

Given these cost pressures, industrial companies adjusted pricing carefully. Many increased their end-product prices to protect margins, especially in markets with steady demand.[2] For instance, heavy equipment and machinery producers faced tariff-inflated input costs that raised prices on their equipment, which ultimately made infrastructure and construction projects more expensive. Auto manufacturers warned that new car prices would rise (one estimate was an increase of ~$200–$300 per vehicle from metals tariffs alone).[9] However, price elasticity played a role – in highly competitive or price-sensitive segments (e.g. economy cars), producers were cautious, sometimes accepting lower profit rather than risk losing customers.

Notably, demand for big-ticket manufactured goods like autos can be price-elastic: consumers may delay purchases or buy used vehicles if new prices jump too much. There is evidence that in regions hit hardest by trade retaliation (which squeezed farm incomes and raised uncertainty), purchases of new automobiles declined, suggesting consumers pulled back when costs climbed.[10] For more essential or less substitutable industrial purchases (e.g. replacement parts or B2B machinery), buyers largely had to absorb the increases or seek alternative suppliers. Overall, U.S. manufacturers found that the ability to pass on costs depended on the product and competitive landscape – many did push through price hikes (as seen with appliances and equipment), while others tried to mitigate or delay increases to maintain market share.

Supply chain adjustments and sourcing

To blunt the tariffs’ impact, manufacturing firms aggressively restructured supply chains. Companies like Ford and General Motors reevaluated production locations and supplier choices in response to Chinese import tariffs.[2] Some shifted procurement to domestic or non-Chinese suppliers (e.g. sourcing electronic components from Taiwan or Mexico instead of China) to sidestep the tariffs. Others negotiated discounts with suppliers or explored alternative materials. In certain cases, manufacturers accelerated automation and localization – for instance, foreign appliance makers moved some production to U.S. factories (hiring American workers) to avoid import taxes.[11] While such moves can eventually lower exposure to tariffs, they often involve upfront investment and time, meaning short-run price impacts were still felt.

Domestic vs. international sourcing became a balancing act: tariff costs made foreign inputs costlier, but domestic inputs (like U.S. steel) also grew pricier due to reduced competition.[6] Many firms thus faced higher costs regardless of source in the near term. Over the years of 2018–2019, the “China supply” for U.S. manufacturers shrank substantially – one index shows China’s share of U.S. low-cost country imports fell by over 10 percentage points as companies diversified to other countries.[12] However, few firms could fully replace China overnight, meaning supply chain disruptions (delays, requalification of new suppliers, etc.) occasionally led to production bottlenecks or inventory shortfalls, which in turn put additional upward pressure on prices for available goods.

Industry-specific outlook

Within manufacturing, steel-intensive sectors were hit especially hard on costs. The construction industry, for example, saw sharp increases in the price of structural steel, rebar, and other inputs – raising building costs. Construction firms had to charge more for projects or absorb costs, squeezing margins.[2] Similarly, makers of farm equipment, industrial machinery, and aerospace parts (all reliant on specialty metals) experienced cost inflation that ultimately filtered into higher equipment prices or leasing rates.

Automotive manufacturing felt a dual impact: tariffs on metals raised the cost of car bodies and engines, while tariffs on Chinese parts (electronics, tires, etc.) increased component costs for many models. This contributed to more expensive vehicles for consumers and higher repair part prices.

Consumer appliance and electronics manufacturers (discussed more below) also straddle this category – those that assemble in the U.S. with imported parts faced tough choices to raise appliance prices (as seen with washing machines). The net effect for manufacturing and industrial goods has been significant inflationary pressure on goods prices, partially offset by strategic sourcing shifts and efficiency efforts. Even so, price increases in this sector outpaced those in tariff-exempt sectors during the trade war period, illustrating the relatively inelastic supply for critical inputs: when faced with import taxes, costs rose broadly and were largely passed through to customers.[2]

Consumer Goods, Retail, and Franchises

Direct and indirect cost impact

Tariffs on Chinese goods hit the consumer sector broadly, given China’s role in the supply chain for everything from electronics and appliances to apparel, furniture, and toys. Initially, the 2018 tariffs targeted industrial goods, but by 2019 many consumer products were on tariff lists, including clothing, footwear, household goods, and electronics. This raised the landed cost of imported inventory for U.S. retailers and consumer brand companies.

For example, a 10% tariff on electronics components and gadgets directly increased costs for firms like Apple, which rely on Chinese assembly of smartphones and laptops.[2] Likewise, apparel and home goods retailers faced higher prices on goods sourced from China (though some staple apparel categories were eventually excluded or faced delayed tariffs). In aggregate, the added import duties forced consumer-facing companies to contend with higher unit costs. Some of these were passed down the chain: shoppers began to see price tags creep up on certain products. A CBS analysis in mid-2019 noted that consumers should expect to pay more for popular imported items – from TVs and appliances to shoes and bikes – as retailers factor in tariffs.[13]

Even where the final assembly wasn’t in China, tariffs on Chinese-made components (e.g. microchips, fabrics, or packaging materials) indirectly raised costs for U.S. consumer goods manufacturers. Indirect effects also came via commodities: for instance, tariffs and retaliatory measures disrupted agricultural trade, sometimes raising input costs for food products (e.g. if a food company had to source more expensive domestic soy or pork due to lost import options).[2] In summary, the consumer goods sector saw a broad-based cost increase on internationally sourced merchandise, both through direct tariffs on finished goods and indirect cost inflation in supply chains.

Pricing and consumer behavior

Companies in retail and consumer products had to decide how much of the tariff-induced cost to pass to consumers versus absorb in margins. In practice, many implemented selective price hikes, especially on less price-sensitive or higher-end items. For everyday low-cost goods, large retailers were cautious – highly price-competitive segments (like basic apparel or groceries) saw retailers try to hold prices steady by pressuring suppliers or shifting sourcing.

Nonetheless, consumer prices did rise in affected categories. For instance, one detailed study found U.S. import prices from China increased nearly one-for-one with the tariffs, and American buyers paid the difference, indicating minimal foreign price adjustment.[3] Shoppers gradually noticed higher prices on imported electronics, appliances, and some household items. Anecdotally, big-box retailers like Walmart warned of price increases, and some passed on a portion of the tariffs to consumers in the form of a few extra dollars on certain goods.

Consumer behavior began to adjust: there were reports of stockpiling and “buy ahead” behavior (e.g. consumers and businesses buying appliances or tech gear before scheduled tariff hikes). After prices rose, consumers sometimes substituted or deferred purchases – for example, if a particular brand became too costly due to tariffs, shoppers might switch to a non-tariffed alternative brand or forego an upgrade cycle for electronics.

Overall consumption remained resilient in 2018–19 (given strong employment and wage growth at the time), but price elasticity varied. Demand for essential or hard-to-substitute goods (e.g. smartphones or kids’ toys during holidays) proved inelastic – consumers paid the higher prices. In contrast, for goods with alternatives, higher prices pushed consumers to seek bargains (boosting discount retailers and second-hand markets). Notably, U.S. retailers with diverse sourcing could sometimes offer lower price increases than competitors tied to China, influencing consumer choices.

Supply chain and sourcing strategies

The consumer goods sector undertook rapid supply chain pivots to mitigate tariffs. Retailers and brand manufacturers diversified their supplier base, moving orders to countries like Vietnam, India, Bangladesh, Mexico, and others not facing the new U.S. duties.[5] For example, apparel companies increased sourcing from Southeast Asia; electronics manufacturers shifted some assembly to Taiwan, Vietnam or even back to North America. Large retailers with global supply chains (e.g. Walmart, Amazon) leveraged their scale to negotiate better terms and reroute product flows.[2]

In some cases, franchises and consumer brands tapped domestic suppliers more heavily for inputs or products, though domestic capacity and higher domestic prices limited this option in many categories. To illustrate, a franchise-based furniture retailer might start buying more U.S.-made furniture to avoid China tariffs, but find domestic manufacturers also raising prices due to their own cost pressures (wood, metal, etc.), offering only partial relief. Many companies resorted to creative strategies: altering product designs to use tariff-free components, utilizing bonded warehouses and duty drawback programs, or shipping goods through third countries after minor processing to reduce tariff exposure. These shifts helped contain some price increases but often came with added logistics costs.

Supply chains grew more complex, and some smaller import-reliant businesses struggled to adapt, at least in the short term. For franchisors – especially those in retail or food service – the challenge was to guide franchisees through cost management (e.g. finding new approved suppliers or adjusting menu prices). A positive outcome for consumers was that retailers’ aggressive sourcing shifts sometimes prevented the worst price spikes. In fact, by late 2019, imports from China had decreased sharply, while imports from other low-cost countries rose commensurately, indicating successful circumvention in many cases.[5] Still, such adjustments were not cost-free, and they underscore how tariffs prompted a reconfiguration of global sourcing for consumer goods.

Sector-specific impacts

Different consumer industries felt varying degrees of pain. Consumer electronics were a focal point – tariffs on components and finished electronics (on List 3 and List 4 tariff lists) meant higher costs for items like smartphones, laptops, TVs, and smart home devices. Analysts projected that consumer electronics prices would rise and indeed, certain products saw notable increases or smaller-than-normal price drops year-over-year. For example, one estimate suggested the final round of tariffs could boost U.S. consumer tech prices by several percentage points, contributing to an overall core inflation uptick.[14] Retail apparel and footwear had a narrow escape in that tariffs on most clothing were delayed until late 2019 and then partially suspended, yet uncertainty drove retailers to diversify sourcing proactively. By shifting production to tariff-free countries (e.g. more apparel imports from Vietnam, which gained a big share of the shift, many clothing retailers avoided major price hikes, resulting in only mild inflation in apparel.[5]

Appliances and home goods saw more direct increases (as noted, washers/dryers spiked, and other home appliances faced cost pressures). Franchise businesses in the food sector experienced indirect effects: tariffs on imported foodstuffs (and retaliatory tariffs abroad) influenced commodity prices. For instance, U.S. tariffs on European foods (like cheeses, olive oil, wine) in a separate dispute raised costs for restaurants and food retailers sourcing those items. Fast-food franchisors mainly source domestically, so they were largely insulated except for higher prices on packaging or kitchen equipment imported from abroad. Franchises in retail (toys, auto parts, etc.) mirrored the impacts discussed – those reliant on imported inventory saw costs rise and had to adjust pricing or sourcing.

In summary, consumer-facing sectors navigated the tariffs by tightly managing pricing strategies and supply chains: passing on only what the market could bear, finding new suppliers, and in some cases accepting thinner margins to keep customers. The outcome was a patchwork – some product prices climbed significantly, while others were stable due to successful mitigation. But overall, U.S. consumers faced higher inflation on many goods than they otherwise would have, directly attributable to the tariffs.[2]

Healthcare & Pharmaceuticals

Tariff exposure

The healthcare sector – including medical devices, healthcare services, and pharmaceuticals – was comparatively less affected by Trump-era tariffs than manufacturing or consumer goods.[2] Many critical medical supplies and drugs are either produced domestically or sourced from trade partners with favorable terms. Recognizing the vital nature of health products, U.S. policymakers were cautious about imposing tariffs that could raise medical costs. In practice, a significant share of medical equipment and pharma imports were excluded from the tariff lists or saw tariffs lifted quickly to avoid shortages (for example, certain medical devices initially on the China tariff list were granted exemptions).

Domestic production of pharmaceuticals (especially generic drugs) and medical devices is substantial, and those domestically made products did not incur new costs from tariffs.[2] Thus, the direct impact on input costs for U.S. healthcare providers was limited. There were some areas of exposure – for instance, medical imaging equipment and advanced devices often include components from China or Europe. Tariffs on electronics could indirectly raise costs for imaging machines or hospital IT hardware. Additionally, China is a major supplier of certain pharmaceutical ingredients and medical consumables; while most of these weren’t explicitly tariffed, any that were would raise costs for drug manufacturers. On balance, though, healthcare supplies were largely shielded by exemption due to their critical status.[2]

Pricing and inflation in healthcare

Given the minimal direct tariff impact, the overall pricing of healthcare services and products in the U.S. did not see a notable tariff-driven spike. Healthcare inflation in 2018–2019 was driven mostly by factors like labor, R&D costs, and hospital services, rather than import costs. If a medical product did face a tariff, typically the government or hospitals acted to ensure continuity of supply, sometimes absorbing costs or fast-tracking alternative sourcing.

For example, if a particular Chinese-made medical device suddenly cost more, a hospital might procure a substitute from Europe or a domestic manufacturer (even at a slightly higher base price) to avoid paying the tariffed item’s cost. Because healthcare demand is relatively inelastic (patients need treatments regardless of cost), any necessary price increases due to tariffs would likely be passed through to insurers or consumers. However, thanks to the shielding of most medical goods, patients and healthcare providers largely avoided tariff-related price hikes on medicines and equipment. Pharmaceuticals were explicitly spared from tariff lists to prevent driving up prescription drug prices (a politically sensitive issue). As a result, there was no observable uptick in drug prices attributable to tariffs – changes in drug pricing came from other supply/demand dynamics.

Supply chain and sourcing shifts

Even though direct tariff effects were small, the healthcare industry took note of supply chain vulnerabilities highlighted by the trade war. Medical manufacturers diversified sourcing for key components as a precaution. For instance, a medtech company that sourced 100% of a device component from China might qualify a second supplier in Malaysia or the U.S. to hedge against future tariffs or disruptions. The essential nature of healthcare products meant there was strong impetus to ensure supplies were secure and affordable. We saw this play out even more in 2020 during COVID (when PPE from China became critical), but during 2018–2019 the impact was more about prudent strategy than acute disruption.

Domestic vs. international sourcing in healthcare shifted marginally – to the extent tariffs threatened any item, companies looked for tariff-exempt countries or increased domestic manufacturing. Some pharmaceutical firms explored bringing production of active ingredients back to the U.S. or to countries like India not subject to U.S. tariffs. Hospitals also built up inventories of certain imported supplies ahead of tariff implementation as a buffer. These moves were part of a broader trend of ensuring that crucial health supplies wouldn’t be caught in trade crossfire.

Sector resilience and elasticity

Healthcare demand is famously inelastic – people require treatments irrespective of moderate cost changes – which means if tariffs had significantly raised input costs, providers could pass that on in pricing without a huge drop in demand. But since the tariffs largely spared healthcare, this scenario was avoided. The industry remained one of the least affected by the trade war in terms of pricing and inflation.[2] Any cost increases that did occur were minor and often absorbed by large health systems. For example, if a particular imported diagnostic machine became 5% costlier, a large hospital network might negotiate a deal or use capital budgets to avoid raising patient fees.

The U.S. government’s decision to exclude most health-related imports from tariffs was deliberate to prevent healthcare cost inflation. Thus, Riverside’s portfolio companies in healthcare likely did not see material price hikes directly from tariffs. Their focus remained on controlling other costs. One caveat: if a healthcare company uses heavy machinery or vehicles (ambulances, hospital construction, etc.), those capital costs rose due to steel tariffs (as discussed in manufacturing), indirectly affecting budgets. But core medical products stayed stable.

In summary, healthcare and pharma were effectively “sheltered” sectors under the Trump tariffs, with domestic production and tariff exemptions insulating them from the pricing turbulence seen elsewhere.[2] This highlights that critical industries can be treated as special cases in trade policy to avoid public harm.

Business Services, Education, and Other Sectors

Direct vs. indirect effects

Service-oriented sectors such as business services (consulting, professional services, financial services), education and training, and franchised services experienced indirect impacts from the tariffs. Because these businesses do not trade physical goods extensively, there were no direct import taxes on their core activities. However, indirect effects materialized through a couple of channels.

First, general inflationary pressure from tariffs (higher fuel costs for transportation, more expensive office supplies or equipment, etc.) raised the operating expenses for service firms slightly. If a marketing agency needed to buy new computers or office furniture, those items might cost more due to tariffs on electronics and furniture imports, nudging up capital expenditures. Second, and more significantly, tariffs affected the clients and customers of these service sectors. Many business services firms serving impacted industries were hurt indirectly by tariffs.

As those client companies saw margins squeezed by import costs or dealt with supply disruptions, they often looked to cut costs – possibly reducing discretionary spending on consultants, training programs, or IT upgrades. Thus, the tariffs’ broader economic drag could dampen demand for some services. Education and training organizations might have seen enrollment or budgets tighten if companies and consumers felt a financial pinch from higher prices elsewhere. For franchised service businesses (like auto repair franchises, cleaning services, etc.), tariffs could raise the price of supplies and equipment they use (e.g. imported auto parts for repair shops, or cleaning chemicals), which in turn might force a slight increase in service prices to maintain profitability.

Pricing and consumer behavior

In these sectors, any pricing changes were driven more by secondary effects. Business services providers generally price based on value and costs like wages; tariffs didn’t directly figure into their fee calculations except as a minor inflationary factor. If anything, some consulting firms actually increased their services to help clients navigate tariffs (trade compliance consulting, supply chain reengineering advice), potentially allowing them to command higher fees due to high demand for guidance – an ironic silver lining. On the other hand, if a service firm’s clients were cutting budgets, the firm might restrain any fee increases despite a bit of inflation.

Education sector pricing (tuition, course fees) is influenced by many factors; tariffs would only tangibly affect it if institutions faced higher costs (for example, a vocational school needing to buy imported machinery for training would pay more). Such costs could be passed to students through slightly higher tuition or fees, though evidence of this is scant. Consumers generally wouldn’t directly associate tariffs with changes in service prices, as the linkage is indirect.

Franchise services (e.g. a franchised gym or salon) might have to pay more for equipment (treadmills from abroad, salon chairs, etc.) and thus might implement small price increases for memberships or services. However, consumer behavior in services tends to be more influenced by overall economic confidence and wage growth. During 2018–19, the economy was strong, so demand for services remained solid, and any slight price uptick due to tariffs was likely absorbed without major changes in consumer behavior.

In short, service sector pricing saw little direct tariff-driven volatility – any increases were modest and often blended into general inflation.

Adaptation and strategy

Service businesses did not need to overhaul supply chains like goods manufacturers did, but they still adapted strategically to the new environment. Consulting and logistics firms, for instance, incorporated tariff impact analysis into their offerings, effectively turning the trade war into a consulting opportunity. Some firms locked in longer-term contracts for supplies (fuel, office materials) to hedge against rising prices. Education providers sourcing lab equipment or technology for classrooms sought domestic vendors or alternative suppliers to avoid tariff premiums. Franchisors supported their franchisees by bulk-purchasing equipment to get better deals in spite of tariffs, or by finding tariff-exempt sources for necessary products.

In terms of domestic vs. international sourcing, most inputs for services (like labor and local supplies) were domestic by nature, so there was not a dramatic shift there. One notable area is energy and utilities (often categorized under services in macro terms): tariffs on imported industrial components could affect utility infrastructure costs, but utilities often source domestically; moreover, energy commodities like oil and gas were not directly tariffed by the U.S. (though Chinese retaliation on U.S. energy exports did impact global prices slightly).

Overall, service industries demonstrated high resilience – they leaned on domestic inputs and had flexibility in passing minor cost changes to clients without major restructuring.

Price elasticity considerations

Services generally have different demand dynamics than goods. The “price” of a service is often a function of wages and expertise rather than material costs. Thus, the tariff-induced cost changes (fuel, equipment, etc.) that did occur were a small fraction of total costs for most service firms. Many could adjust prices marginally or not at all, since strong economic conditions allowed them to maintain or even raise prices based on demand, not input costs. For instance, a legal firm or financial advisory might raise rates in 2019 due to high demand and good results for clients, not because tariffs forced them to. If clients faced financial stress from tariffs, some service providers might offer temporary discounts or value-added services to keep those clients.

Education services often have more rigid pricing (academic year tuition set in advance), so any cost changes would be factored into future budgets. Franchise businesses serving consumers had to be mindful of price sensitivity: if, say, a car repair franchise faces costlier imported spare parts, it might charge slightly more for repairs, but since car repair is often necessary (inelastic demand), customers would likely pay the difference. Meanwhile, those customers might cut back on more elastic services (like dining out or entertainment) if overall inflation pinched their wallet – illustrating how tariffs’ inflationary effect can indirectly shift consumer spending patterns among services. In sum, business and education services saw low direct pricing impact from tariffs, and their fortunes were more tied to the broader economic ripple effects (like changes in client spending and confidence). These sectors remained comparatively stable in pricing, especially compared to the turbulence seen in manufacturing and trade-heavy industries.

Conclusion: Cross-Sector Pricing Impacts and Outlook

The introduction of tariffs under the first Trump administration set off a chain reaction of cost increases and adaptive responses that varied by industry. These impacts are being seen in the most recent tariff activities. Inflationary pressure was most acute in sectors with heavy exposure to imported inputs – manufacturing, industrial goods, and many consumer products saw tangible price increases as tariffs raised production costs.[2 11] In these sectors, companies passed on a significant share of costs to customers, contributing to higher consumer prices (e.g. appliances, electronics, vehicles) and fueling modest overall inflation.[14] More sheltered industries – notably software, digital services, and much of healthcare – experienced little direct pricing impact, yet were impacted by indirect downstream pressure on costs and spending.[2] Supply chain disruptions emerged as a unifying theme: across the board, businesses reexamined their sourcing. Many achieved partial cost relief by shifting supply chains (for instance, moving manufacturing from China to Vietnam or sourcing metals domestically), but these moves often entailed transition costs and complexity.[2 5] Domestic suppliers, while benefiting from reduced foreign competition, often raised prices themselves, which blunted the advantages of onshoring.[6 3]

From a consumer standpoint, the tariffs functioned as a tax that rippled through to retail prices in varied ways.[2] Shoppers faced higher prices on certain goods, and while strong income growth at the time helped absorb the impact, there were adjustments in buying behavior (seeking deals, delaying purchases of pricier items). Businesses responded by innovating in pricing and supply strategy: some bundled products to hide price increases, others scaled back features to maintain price points, and discount retailers gained ground by offering lower-cost alternatives. Price elasticity differences were evident: where demand was flexible, companies trod carefully on price hikes; where products were necessities or had fewer substitutes, prices climbed more freely. For example, the relatively inelastic demand for construction materials meant builders paid more for steel and simply passed costs into home prices, whereas highly elastic markets like apparel saw companies rapidly switch suppliers to avoid raising clothing prices and losing customers.

In sector-by-sector terms, Specialty Manufacturing & Distribution companies in Riverside’s portfolio would have encountered higher input costs and likely raised prices or surcharges on products, though mitigated by sourcing tweaks. Consumer brand businesses might have adjusted product mixes or supplier bases to control retail pricing, but still felt a squeeze in margins and selective price increases on goods. Healthcare companies were largely spared direct tariff costs, maintaining stable pricing, while software/IT firms had to manage hardware cost upticks without derailing their service pricing. Business service providers continued to price mainly on value but kept an eye on clients’ tariff troubles, sometimes adjusting contracts accordingly.

Overall, the Trump-era tariffs produced a broad but uneven inflationary effect across the U.S. economy. Estimates suggest they added on the order of 0.5 percentage points to U.S. inflation and acted as a significant cost shock to globally integrated industries.[14] The broader ripple effects – including retaliatory hits to exports, reduced efficiencies, and uncertainty – compounded the direct price effects, potentially restraining investment and productivity growth.

For Riverside and its portfolio sectors, the key takeaways are that pricing must be managed dynamically in a tariff environment: companies that swiftly adapted their supply chains and pricing strategies were able to maintain growth, while those that couldn’t saw margin compression or had to push steep price rises to customers. The data show that tariffs undeniably raised costs of goods and services in targeted areas, and those costs were largely passed through to U.S. prices.[2 3] Going forward, firms have learned to build in contingencies for such trade policy shocks – whether via diversified sourcing, flexible pricing mechanisms, or inventory strategies – to protect against sudden cost surges.

In conclusion, the Trump tariffs left a legacy of slightly higher prices and a restructured supply chain landscape, illustrating how trade policy can send inflationary tremors through virtually all sectors of the economy that impact every industry through direct and indirect impacts.[2 15]

Sources

- 1 – Trump Tariffs: The Economic Impact of the Trump Trade War

- 2 – The Impact of US Tariffs: Which Industries Are Most and Least Affected

- 3 – Trump’s tariffs on Canada, Mexico, and China would cost the typical US household over $1,200 a year | PIIE

- 4 – Economic Research: How Might Trump’s Tariffs–If Fully Implemented–Affect U.S. Growth, Inflation, And Rates? | S&P Global Ratings

- 5 – Trade war spurs sharp reversal in 2019 Reshoring Index, foreshadowing COVID-19 test of supply chain resilience

- 6 – How Steel Tariffs Affect Your Metal Building Price | General Steel

- 7 – What Trump’s Aluminum and Steel Tariffs Will Mean, in Six Charts

- 8 – The spillover effects of trade wars

- 9 – [PDF] Tariffs/Automotive – Proactive Worldwide

- 10 – Steel Tariffs and U.S. Jobs Revisited | Econofact

- 11 – The spillover effects of trade wars

- 12 – Trade war spurs sharp reversal in 2019 Reshoring Index, foreshadowing COVID-19test of supply chain resilience

- 13 – Trump’s tariffs on Canada, Mexico and China are in effect. Here’s …

- 14 – Economic Research: How Might Trump’s Tariffs–If Fully Implemented–Affect U.S. Growth, Inflation, And Rates? | S&P Global Ratings

- 15 – Tariffs explained: your macro questions answered | EY – US